Juneteenth is more than a date on the calendar – it is a mirror held up to our collective memory as Black Americans. It reminds us that freedom, for us, has never simply been declared; it has always been demanded and too often delayed. The reality that some of our ancestors didn’t know they were free until after the Emancipation Proclamation is not just a historical fact – it’s a metaphor for the continued struggle against systems that promise liberation but deny its full reality.

From emancipation to Jim Crow, from redlining to mass incarceration, our journey is an active reminder to continue the work. It asks us to honor the past not only in times of national recognition, but in our daily choices to teach and build upon the foundation laid by those who came before us.

Juneteenth stands as a solemn call to honor those who struggled with no promise of arrival – and a vow that their fight was not in vain.

The Rev. Dr. Kenneth Davis, now in his 80s, stands as a living link to that era.

Roots in Argo

Before the South Side of Chicago shaped him, the Rev. Dr. Kenneth Davis was grounded in the soil of Argo, Illinois – a small industrial town just outside the city. For Black families migrating north from the South, Argo offered more than factory jobs as an incentive for the Great Migration. It was a place to plant roots, raise children, and build lives in defiance of the odds stacked against them. Argo represented a legacy of self-determination.

“My grandfather was one of the first settlers to come up from Georgia to Argo,” Davis recalled. “People came to work at [Argo] Corn Products–where they made Argo starch, Bosco, all kinds of things from corn. That’s what built the town.”

“Fred Hampton’s daddy was from Argo. My people had businesses, bars, and homes right there. We had giants come out of that little place,” he said. “That was my root. We were a close-knit community.”

Davis started school at just four years old. “I told them, ‘I sure will be glad when I can go to school – so I can read and write and y’all can’t keep no secrets from me,’” he laughed, recalling how his mother and her friends would spell words to speak in code around him.

His family later moved to Altgeld Gardens, a wartime housing development on Chicago’s far South Side – built for Black laborers but located atop a former nuclear waste site.

“Dirt roads, no paved streets,” he said, “but it was a tight-knit, working-class Black community. That’s where I came from.”

Still, life in Chicago was no refuge from racism.

“Chicago racism is a different kind,” Davis said. “Sophisticated racism. You didn’t always see it, but you felt it every day.”

From segregated parks to housing discrimination, the reality of systemic exclusion shaped his boyhood.

“When we passed Palmer Park, we saw the swimming pool – but we couldn’t go in. We had to fight just to get into public spaces that were supposed to be for everyone.”

The struggles in the South were also unfolding in his own backyard.

At Jackson Park Golf Course – one of the only places where Black people were allowed to play – he and a friend once tried to hustle golf balls for snack money. Instead of getting in trouble, they were mentored by Black golfers who turned them into caddies.

“That’s how I met people like Joe Louis,” he said. “But even there, they shot over the fence at us. Just for being there.”

The experience of resistance wasn’t abstract. It was a lived, daily fight.

“In the streets, in the schools, in the workplaces. We fought because we had no other choice.”

Nothing brought that reality closer than the murder of Emmett Till. Till’s family lived just a few doors down.

“He slept in the bed next to me the week before he went to Mississippi and died,” Davis said.

He attended Till’s open-casket funeral, a memory that still haunts him.

“My mama fainted when she looked in that casket and saw that boy. I wanted to kill every doggone thing I could. That image of Emmett still lives in me. I remember how I felt. I still see that.”

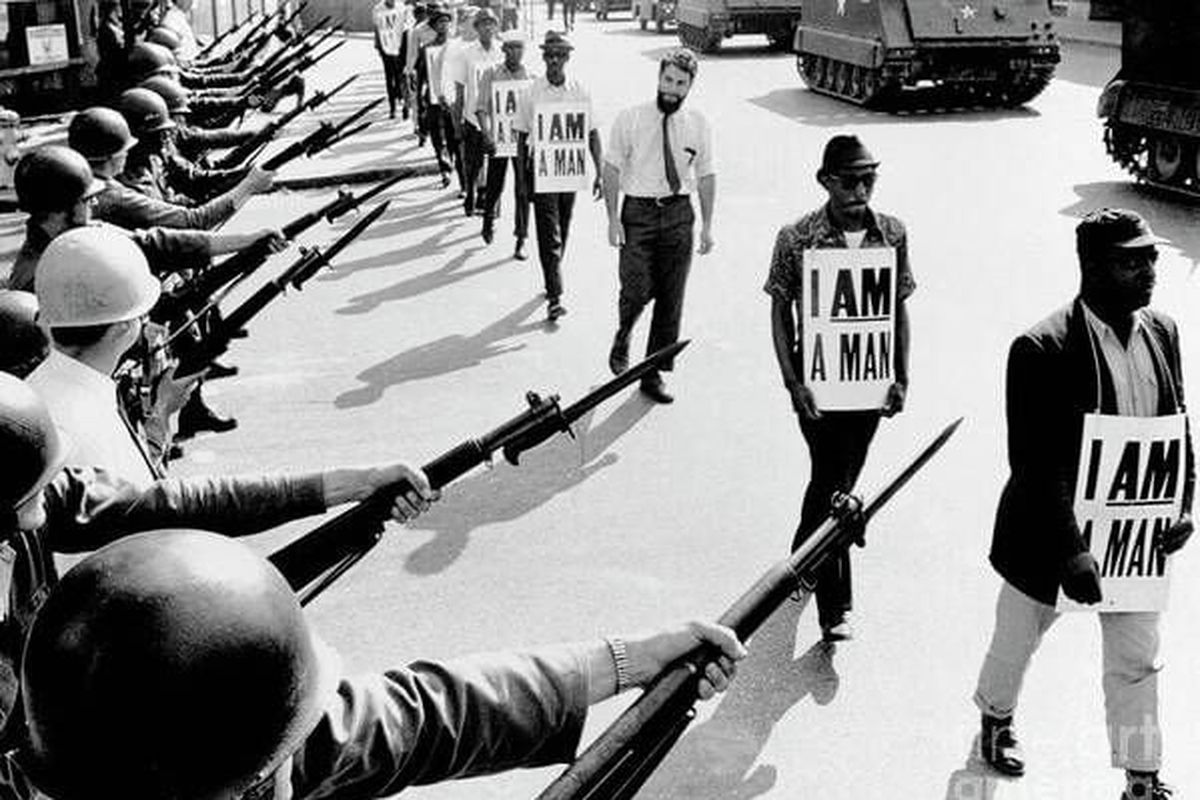

As he spoke those words, the intensity of the fury that racial hatred invoked was almost tangible – an unembellished and grim reminder of why we must fight. Davis didn’t just learn about history – he lived inside it. The community that raised him was a battleground, a classroom, and a crucible that helped shape the young man who would one day wear the iconic “I Am a Man” sign on his chest – now a photographed remnant of struggles not far removed from the present day.

Becoming the Movement

Davis began protesting as a youth in the belly of the beast, organizing in his community, and eventually stood shoulder to shoulder with civil rights giants. His path was not always straight.

“I didn’t know how I ended up in a nonviolent movement,” he admitted. “I come from a place where we fought back.”

He remembers meeting Malcolm X in his earliest days as a minister, fresh out of prison and still finding his voice. On one occasion, Malcolm visited the housing projects where Davis lived, speaking at a local children’s center. Davis recalls watching him at the blackboard, developing as a young leader still shaping his message and presence.

As he came of age in a world steeped in racial tension, Davis found himself among men and women who, like him, were searching for a different path to liberation – figuring it out as they went along. He recalls candidly meeting and learning from Dr. King as he became enmeshed with other fired-up freedom fighters, all determined to grab the world by the tail in the name of justice.

“Dr. King would referee us. He’d get us all in the room, and we didn’t always agree, but he’d pull us together,” Davis said. “He talked to us about unity through adversity – that even when we don’t see eye to eye, we have to find one thing we all agree on and fight for that.”

He still carries the weight of one of Dr. King’s most pressing questions: “Where do we go from here? That question still sits with me.”

For Davis, it’s a lasting reminder that unity isn’t automatic – it’s something we must choose.

In reflecting on how we work together across differences, our conversation moved toward a powerful metaphor. In the Bible, Peter was fiery and bold – quick to act – while John was gentle and full of love. This example demonstrates that every kind of leadership, every style of communication, has a purpose. Unity doesn’t mean uniformity. It means recognizing the value in each other’s gifts and standing together with a common goal. You need a Peter, and you need a John.

“We’ve got to stop letting doctrine or denomination divide us,” he added. “Let’s stop fighting over differences,” he said. “And start loving one another enough to rise together.”

The Burden of Memory

Now in his elder years, the Rev. Dr. Davis is unrelenting in his message: we must tell the truth about the past. “That’s where people like me come in.” He worries that today’s youth are disconnected from that history. “They think we’re lying when we tell our stories,” he said, noting the absence of elders in many family structures and the generational trauma that remains unhealed. “We were taught to hate ourselves. That’s the worst damage racism has done.”

On Love, Legacy and Liberation

From critiques of Black elitism within social class, to the fractures caused by assimilation, Davis doesn’t shy away from the hard truths. But he also leaves space for restoration. “My generation laid the foundation. Yours has to build the house. Start with love.”

He is not just a witness to history, but an elder whose voice still speaks with urgency. As he now sits and tells the history that we watch in documentaries or read about in books, he has one final word. Over 60 years after he marched in city streets, facing Jim Crow and taking risks, he still says he gets mad about injustice.

“But I ain’t giving up. And neither should you.”