For Dr. Bob Bartlett, the land is more than a backdrop. It’s a living memory, a spiritual inheritance – a path to personal and collective rejuvenation. His dream of launching an environmental leadership camp for BIPOC youth isn’t just about teaching skills or exploring nature. It’s about restoration and responsibility – of self, of culture, and of the stewardship BIPOC people once held of the earth.

“This came out of pure selfishness,” Bartlett admits. “I was born and raised in the country with Black folks who loved their rivers and their mountains … I grew up learning to hunt, to fish, to trap, to live off the land with Black folks in a racially divided town.” But that relationship, he explains, was gradually lost. Moving West after the Vietnam War, Bartlett spent decades as an avid outdoorsman – hiking trails, fly fishing, and working in environmental justice circles – without once encountering another Black angler.

It wasn’t until 2020 that he met his first Black fly fisherman.

“That’s when I realized there was a huge hole – heart, soul – in my life,” Bartlett said. “It took a lot of reflecting to figure out what that hole was about. And I’ll tell you – that it was missing being with people like us outdoors.”

This void is what inspired Dr. Bartlett to create Ubuntu Fly Anglers – a community of BIPOC fly anglers brought together through their shared love of nature. What began as a way to find fellowship has grown into a larger project aimed at resurrecting BIPOC voices in fly fishing and environmental spaces.

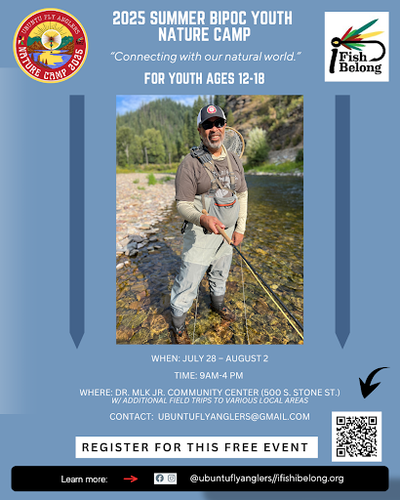

Bartlett now hosts a podcast, where he shares conversations with other BIPOC anglers and outdoor enthusiasts. This summer, supported by grants, he plans to launch a weeklong environmental leadership camp for those who self-identify as BIPOC youth from July 28 to Aug. 2. For him, this is a way to pay it forward by nurturing a new generation of leaders who feel empowered to understand their relationship with the land.

Hosted at the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center, the camp will include field trips, classroom learning, and hands-on fly fishing. It is designed to be small and intimate, serving no more than 15 students from Spokane’s Northeast and East Central neighborhoods. Open to youth ages 12 to 18, the camp is completely free – transportation and meals will be provided.

But its impact is meant to be far-reaching. For Bartlett, this is legacy work –challenging internalized disconnection from land and countering the damage of generational oppression. This is about ownership.

“We used to live in relationship with nature,” he said. “We owned our own property. We owned the land. We grew our food. We could withstand downturns in the economy because we didn’t need money.”

But capitalism, he says, changes everything. It has commodified the earth and reduced people, particularly BIPOC people, to tools of extraction.

“Capitalism says we need to put a value on things,” Bartlett said. “That tree? The only value it has to me in a capitalist society is what I can turn it into – for my wellbeing – not realizing that the opposite is true. That tree provides shade, provides oxygen, provides carbon dioxide, and cools the planet.”

The consequences of this worldview, he says, are deeper than environmental destruction–they are psychological and spiritual. He’s witnessed firsthand how nature has transformed people’s lives, often at the edge of crisis.

Take Scot for example. “His father was incarcerated. He became a gangster. Youth gangster, drug dealer in high school,” Bartlett recalls. “He’s (now) a fly fishing guide. His life changed – changed because of his connection with nature.”

Bartlett says these stories are not rare. “So I know from personal stories, testimony after testimony after testimony – how fly angling, being outdoors, has saved people like us. Completely flipped their world around.”

He shared the story of Ashley, a Black hunting and fishing guide in Minnesota. Ashley nearly ended his life after a traumatic medical emergency involving his wife and child. After firing therapists, it was a counselor who finally offered a different approach: to meet not in an office, but outside. They walked. Then hiked. And eventually, Ashley found himself standing in a river, fly rod in hand. That moment, Bartlett says, saved him.

“It is being among something, in something, that you did not create,” Bartlett reflected. “The trees. The river. The fish. There’s that in and of itself – that feeling of being vulnerable. Humbled by it.”

For Bartlett, this is sacred medicine. Nature doesn’t just soothe – it reawakens.

He recalls a moment in Juneau, Alaska, when the sheer majesty of the mountains and rivers overwhelmed him with clarity. “I called my wife and said, ‘Babe, please send all my fishing, camping, and everything gear to me. I’m in heaven. I’m home.’”

Her response? “‘Sure thing, honey – I’ll send your stuff and your four children. I’m not coming!’ ” he laughed.

But in that humor is something true: the undeniable pull of nature. And it’s that connection to land that Bartlett wants to pass on to the next generation.

“Fly anglers overwhelmingly evolve into river advocates,” he said. “Because we approach fishing from a different lens.”

Through the camp, youth will learn to fish – but also to listen to elders, revere the power of the earth, learn environmental history and connect to BIPOC outdoor leaders from around the country. Some, like fly-fishing Hall of Famer Joyce Shepherd, will travel to Spokane to mentor and guide. Others will offer a living testimony of what it means to heal in nature.

“If we don’t get them outside and show them that they have the responsibility to be the next river warriors and environmental activists – it’s our bad,” Bartlett said. “Our children’s children won’t have a chance.”