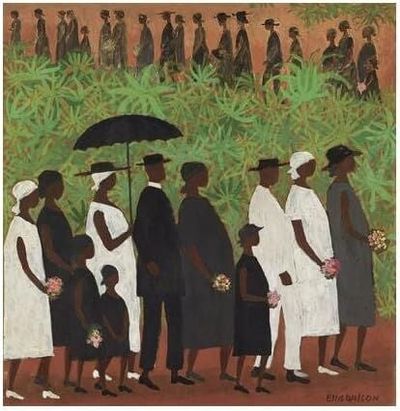

While interviewing Miss Patricia Bayonne-Johnson – genealogist, historian, and one of our beloved columnists at The Black Lens – I was struck by the image that watched over us: The Funeral Procession by Ellis Wilson. Hanging prominently on her wall, the painting served as more than decor; it was a powerful cerebral symbol of Black family, Black tradition, and Black experience. Its presence reminded me how art, like memory, carries us through generations.

Our conversation centered on heritage, lineage, and the enduring connection to family – how these threads shape not just who we are, but how we understand ourselves as part of something larger. As Miss Pat spoke, her words unearthed a deeper conversation: the internalized toll of disrupted narratives, the mental wellness of a people who have endured erasure, and the healing that becomes possible when we choose to remember.

The Funeral Procession, once immortalized in the Huxtables’ living room on The Cosby Show, evoked a sense of familiarity. There, as on Miss Pat’s wall, it stood as a visual sermon – a reminder of reverence, of community, of the sacred responsibility we carry to those who came before us. It was a quiet but unwavering statement: that honoring the past is inseparable from shaping the future.

At that moment, I understood more clearly why Miss Pat has devoted herself to tracing family trees. To know who we are requires more than self-reflection – it demands that we look back, recover what was lost, and pass forward a sense of rootedness. Healing, especially for Black families, cannot happen in isolation. It must happen collectively – with reverence, with remembrance, and with resolve.

Mental health is not separate from our story – it is braided into our kinship ties, generational cycles, and the truths we carry or forget about where we began.

For Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, researching family history isn’t just about names and dates – it’s about restoration. As a genealogist, educator, and descendant of people enslaved by the Jesuits, she has spent decades uncovering her ancestral lineage and empowering others to do the same. She believes genealogy is a healing practice – one that allows Black people to stitch together a fragmented past and reconnect with a sense of self that history tried to erase.

Bayonne-Johnson’s passion deepened after she retired from a long career as a biology teacher. “I was kind of messing around with it after my dad died… but I really couldn’t devote that much time to it because I was a teacher,” she shared. Retirement opened the door to immerse herself in formal research. “One of the first things I did was take a class with the National Genealogical Society… I wrote my final paper about my great-grandfather – the one where my name, Bayonne, comes from.”

That name, and the story behind it, marked the beginning of her journey to reconstruct a legacy often lost to slavery and systemic erasure. “Slavery separated our roots… Cultural identities were stripped away, and individuals were forced to adopt new names, religions, and customs,” she said. “But people have the power to reclaim their histories – and that’s what we do in genealogy. There’s strength in recovery.”

Bayonne-Johnson’s research led to a groundbreaking revelation: she is a descendant of someone enslaved by the Jesuits. Her blog post on this history, published in 2011, went largely unnoticed until 2015 – when it became a catalyst for others trying to trace similar lineages. “Had I not written that blog, they wouldn’t have known how to get started,” she noted. “No one else had put a blog up about Jesuit history – about these people who had been enslaved.”

That recovery– – of names, places, and forgotten kin – is deeply connected to mental wellness, especially for Black Americans navigating inherited trauma and identity confusion. “For me, it kind of anchored me,” she explained. “It gave me a good feeling about myself. I can’t imagine now how I really felt when I didn’t know this information.”

Knowing that her great-grandfather was a free man of color, not enslaved, altered her self-perception entirely. “It meant a lot to me,” she said. “It also brought our families together. We would have a reunion, do research, and bring it forth – it brought us together.”

That sense of belonging, she emphasized, is not a luxury – it’s a human necessity. “Belonging is something all human beings want and need,” she said. “Having a sense of connection throughout time helps make us feel whole.”

She recalled how, when she first received DNA test results pointing to Nigerian ancestry, one of her aunts pushed back. “She said, ‘We didn’t come from Africa.’” That denial, Bayonne-Johnson believes, is rooted in shame. “It was embarrassing to think you came from a slave. It’s like, you didn’t have control of your life – and you did nothing about it.”

That shame is not accidental – it is the result of centuries of dehumanization, historical distortion, and internalized trauma. Being African first is veiled in unfamiliarity for many, not legacy. For countless Black Americans, the starting point of cultural identity is shaped by enslavement, not heritage. After centuries of exploitation and systemic violence, the African origin story has been distorted and propagandized, making it difficult to feel pride in a past that was stripped away. The psychology of being told your beginning is synonymous with bondage creates a quiet, enduring dissonance. Or even having the awareness that there were Black people on American soil before Columbus is an unspoken truth that never made it into Westernized interpretations of history – a truth explored in They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America by Ivan Van Sertima. Yet it is precisely from this displacement that a powerful new sense of self and kin can emerge – one rooted not only in survival, but in reclamation. The act of tracing lineage, speaking names, and embracing ancestral memory becomes a counter-narrative, one that restores dignity and reshapes how we see ourselves.

Shame, fragmentation, and historical neglect all weigh heavily on the Black psyche. “There’s no healing without acknowledgment,” she asserted. “That’s the first step.” Bayonne-Johnson emphasizes that you have to be brave enough to face the chains in your bloodline to begin recovering the fuller truth of who you are. And with that acknowledgment comes a call to action: “Learn your history. Trace them. There’s power in that.”

Despite missing oral history in her own family, she found truth in research. “My paternal great-grandfather wasn’t enslaved – he was free. That was one of the best things I had ever heard,” she said. “Because we assume we were all enslaved.”

Even the act of naming carries generational meaning. “In my family, my grandfather’s name was Nace, short for Ignatius. He named his son that, and then it carried on to a third. And now, babies are being born with that name. We’re passing it on.”

This continuity – through names, stories, and community – is a form of quiet resistance. “Even internally, with all our trauma, we found ways to keep our light going – even without knowing,” she said.

For Bayonne-Johnson, Black Americans are not without roots. “We might not know exactly where we come from, but we come from somewhere. We survived. That means we’re resilient.” She encourages others to go on the journey. “Do the testing. Buy the books. Visit Africa. Learn who you are and where you’re from.”

She reminds us that mental wellness isn’t just about coping with the present – it’s about understanding the past. Our healing depends on connecting the dots between who we are and where we come from. When we trace the patterns in our family stories – of separation, survival, silence, and strength – we begin to mend what was broken. Genealogy becomes more than a historical exercise; it becomes a pathway to wholeness.

“We come from somewhere,” she says – and knowing that, deeply and truthfully, is where the healing begins. Ultimately, she says, “If we don’t tell our stories, someone else will. And when they write it – it’s not true.”